Last month I write a blog post detailing how the current infrastructure strategy to support OTT services isn’t economically sustainable. I got a lot of replies from people with their thoughts on the topic and some suggested that the solution to the platform performance problem will be fixed with better video compression. While it’s a great debate to have, with lots of opinions on the subject, personally I don’t think better gains in compression are the answer.

While a breakthrough in compression technology would allow the current streaming infrastructure to deliver more video, the unfortunate reality is that significant resources have already been invested in, to optimize video compression, and the rate of improvement is far below the video growth rate. Depending on who’s numbers you look at, video streaming traffic is currently growing at a CAGR of about 35%. On the other hand, video compression has improved by about 7% CAGR over the past 20 years (halving the video bitrate every 10 years). Unless video compression has a major breakthrough of 15:1 improvement or more, in compression efficiency, better compression alone cannot solve the internet video bottleneck.

Compression is really about making the video itself smaller and therefore more efficient to deliver and not about the performance of the underlying streaming delivery platform. The benefits of any potential breakthroughs in video compression technology will likely benefit all streaming video delivery platforms equally and, as such, are a separate topic from the requirement to increase the performance of the streaming video platforms themselves.

Similarly, approaches to improve performance by moving popular content to edge devices closer to the customer, such as at cell phone towers and cable head end locations, have been suggested as ways to further improve throughput and capacity. These techniques should all be pursued regardless of what underlying technologies are used to actually stream the video but, unfortunately, these techniques, used separately or even together, offer only incremental benefits to performance. Given the massive scale of the projected demand for streaming video, we need an order of magnitude of improvement in today’s performance in order to address the capacity gap.

To increase the performance of the streaming video infrastructure, there are only two main areas of focus – the software and the hardware. While great strides have been made over the last decade by many in optimizing the streaming video software layers, even the most capable developers are facing diminishing returns on their efforts as additional software optimizations yield progressively fewer performance increases. Continued software optimization efforts will continue to eke out incremental performance gains but are not likely to be a significant factor in addressing the overwhelming capacity gap faced in the industry. By process of elimination, this leaves the hopes pinned firmly on the hardware side of the equation.

Unfortunately, the latest research shows that the performance curve for increases in CPU performance over time has flattened out. Despite increases in the number of transistors per chip, a number that is now approaching 20 billion on the largest CPUs, and the shrinking of the transistors themselves, to sub-10nm in the latest chips, we have reached diminishing returns. The projected increases in annual CPU performance are so far below the 35% annual growth rate in streaming video traffic demand that I think we can eliminate improved CPU performance as a possible solution for the capacity gap problem.

If the software and CPU platform, which has worked so well since the inception of the streaming video industry, cannot meet the future needs of the market, what can? Since the dawn of computing, the solution to insufficient software and CPU performance has been to offload the workload to a specialized piece of hardware. Examples of specialized hardware being utilized to enable higher performance include RAID cards in storage, TCP/IP offload engines in networking, and the ubiquitous GPUs which have revolutionized the world of computer graphics. Thanks to GPU’s, a consumer today can watch 4K video streams on their selection of viewing devices, including televisions, computers, and mobile platforms. Given this track record of success, its seems clear that the innovation that is required is a piece of specialized hardware that can offload the heavy lifting of streaming video from the CPU and software. This technology exists and is now making its way to market thanks to the recent advances in Field Programmable Gate Array or FPGA technology.

Traditionally, FPGA technologies have not been part of the data center infrastructure, but this has begun to change in recent years. In fact, the current edition of the magazine ACMQueue, a publication of the Association of Computing Machinery, features “FPGAs In Data Centers” as its feature article. Early work on implementing FPGA’s in the datacenter was pioneered by Microsoft who, with an effort called Project Catapult, proved that massive increases in the performance of web queries (for the Bing search engine) could be obtained by offloading the workload from the CPU’s and software to FPGA’s. This effort was so successful that Microsoft now deploys FPGAs as a part of their standard cloud server architecture. In order to address the needs of the streaming video industry, an ideal solution would be to offload video streaming to a specialized FPGA, which isn’t a new idea, but something that’s just now being seriously talked about. This would essentially require the implementation of the functionality of an entire streaming video server onto a single chip but, which is both possible and highly advantageous to do so.

Some of those in the industry who know way more than me when it comes to FPGA technologies have suggested new offerings in the market by companies like Hellastorm and others, have the potential to change the way video is distributed. Their solution in particular takes the core functionality of an entire streaming video server and implemented it on a chip the company calls the “Stream Processing Unit”, which eliminates software layers from the data path. The result is that they can offload the heavy lifting of the streaming video workload, thereby freeing up valuable CPU resources to improve the performance of other tasks, dramatically increasing streaming video performance.

Additionally, if the use case requires only streaming video functionality, the CPU, OS, RAM, and much of the other circuitry normally required to stream video can be eliminated entirely, thereby saving significant amounts of electricity. Going forward, the streaming video functionality can follow the hardware performance curve and benefit from improvements to FPGA technologies just as the prior generation of streaming video servers benefited from improvements in CPU technologies. The company claims that their Stream Processing Unit technology will keep pace with advances in networking speeds such that the streaming video being delivered from the platform will fully saturate the networking connection, be it 10Gbs, 100Gbs, and even 400Gbs in the future.

The dual benefits of greater capacity delivered with dramatically less power consumption make video stream offload attractive even before one considers the substantial benefits that can be obtained by freeing up CPU resources to provide other network services. Hardware offload of streaming video, with its ability to rapidly scale in performance over the next few years, appears to be the best way to address the looming capacity gap. Some don’t want to invest in hardware because they feel it has too high of a CAPEX requirement, but based on what we have seen in the market, and from speaking with those who are tasked with dealing with the massive influx of video traffic on the networks, video compression alone isn’t going to solve the capacity gap problem. I am interested to hear what others think can be done to solve the problem in the market, feel free to leave your comments below.

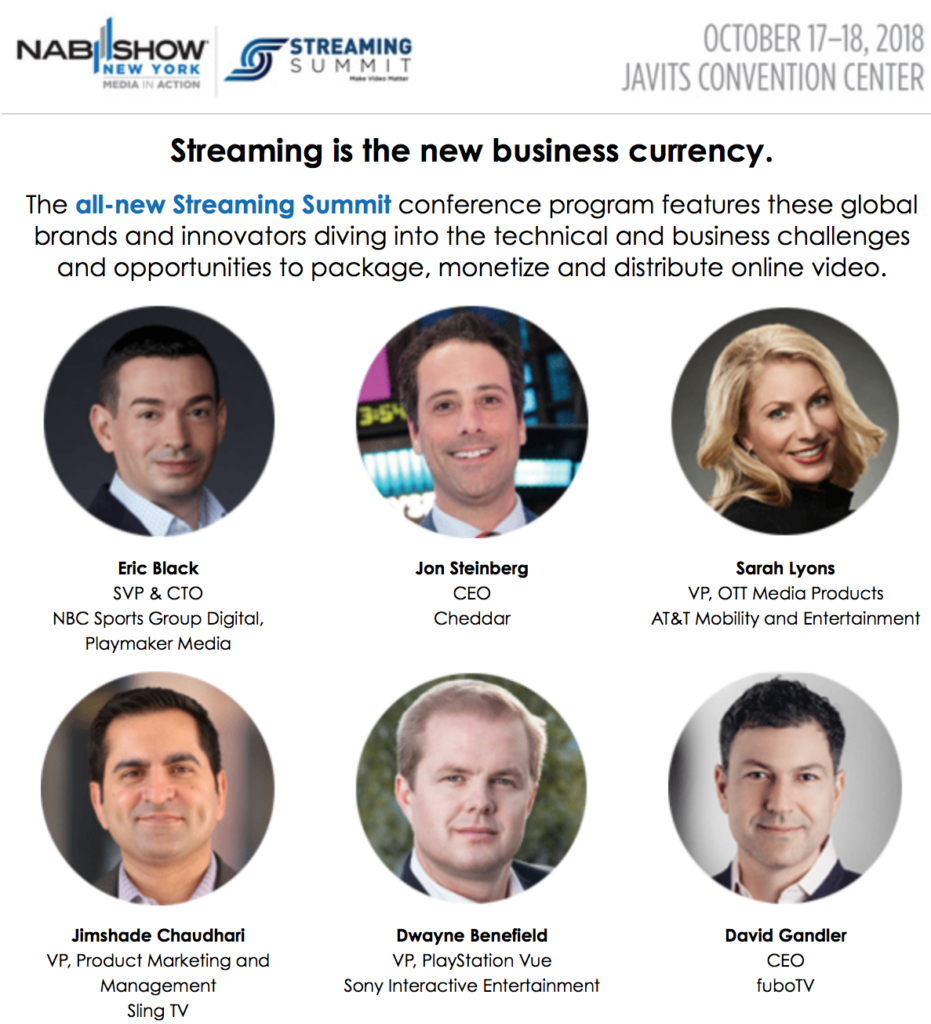

I’m excited to announce that I will be doing ten fireside chats with executives from Sling TV, PlayStation Vue, DirecTV Now, Comcast, Google, Facebook, Cheddar, NBC Sports and Fubo TV – at my Streaming Summit, part of the NAB Show NY, taking place Oct 17/18.

I’m excited to announce that I will be doing ten fireside chats with executives from Sling TV, PlayStation Vue, DirecTV Now, Comcast, Google, Facebook, Cheddar, NBC Sports and Fubo TV – at my Streaming Summit, part of the NAB Show NY, taking place Oct 17/18.

On Wednesday July 25th at 6pm, in association with JNK Securities, I will be hosting a dinner in NYC for Wall Street investors with Fastly’s President (Joshua Bixby), Head of Strategic Partnerships (Lee Chen), and Fastly’s CFO (Adriel Lares). Hot on the heels of another big round of funding for Fastly, the company has spent the past seven years disrupting the CDN market, focusing on performance, security and media delivery.

On Wednesday July 25th at 6pm, in association with JNK Securities, I will be hosting a dinner in NYC for Wall Street investors with Fastly’s President (Joshua Bixby), Head of Strategic Partnerships (Lee Chen), and Fastly’s CFO (Adriel Lares). Hot on the heels of another big round of funding for Fastly, the company has spent the past seven years disrupting the CDN market, focusing on performance, security and media delivery.