NFL Sunday Ticket has kicked off on YouTube and I will be live blogging what I see all day at this post.

I am testing across many devices, with multiple accounts, and have users in other states also providing me with direct feedback. I’m also watching the Reddit message boards, Twitter, and the live chat within games on the iPad. I haven’t seen any reports of streams being down but am seeing LOTS of comments around issues tied to games being blacked out which is expected, but is confusing many.

Mobile and web do not support multiview and YouTube is offering a pre-defined listing of multiview streams. Even with YouTube making that very clear, you see many viewers complaining they can’t pick the games in multiview individually. NFL Sunday Ticket games have distinct source feeds broadcast in 1080i (a mix of native and upscaled) compared to 720p local broadcasts. There is no 4K streaming of NFL Sunday Ticket.

Updates Below:

9:30pm ET: YouTube had a great first week streaming NFL Sunday Ticket. The majority of user complaints were tied to things out of YouTube’s control, like blackout rules, or were as a result of users not understanding that multiview wasn’t supported on desktop or mobile. YouTube has been very clear with their support pages and promoting what the service would and would not provide. There were some issues on YouTube’s side with location services not working right, pixelated streams [1], [2] and playback errors [1], [2], [3], but nothing I saw to indicate it impacted the majority of users. It is unknown if YouTube and the NFL will put out any viewership numbers after week one but if they do, I will add those numbers to this post.

6:27pm ET: I don’t know how YouTube was handling support calls for today but there were more than a few complaints online of consumers being “disconnected” after being put on hold and “hung up on,” once they got through to someone. Also, long hold times of over 2 hours. Hopefully YouTube support will get fewer calls in week two with users having learned the limitations of the service but don’t count on it.

5:50pm ET: Some fans are using the multiview feature to their full advantage. Many have shared photos of their multiview setups on Twitter. So far, I haven’t seen any major technical issues around multiview aside from some games freezing or buffering, which is always going to happen. But I have not seen those complaints in any large quantity.

4:50pm ET: It’s interesting to note just how many ad breaks don’t have ads in the stream and show random images instead. I don’t know if that’s because they are unsold or YouTube TV doesn’t have the rights to show them but many ad spots are “house ads” for YouTube TV.

4:30pm ET: On a side note, regarding YouTube TV the company has acknowledged that on the Apple TV 4K device the ESPN 4K channel is currently limited to 1080p60 quality. YouTube TV support says this problem was expected to be addressed with a prior large Apple update in April but apparently it has not been fixed.

4:15pm ET: Individual game streams on YouTube desktop and mobile don’t show how many users are watching the stream, but the Week 1 Preview Show did show the number watching, which I saw peaking at just over 11,000 at 12:42pm ET.

4:00pm ET: YouTube is aware of an issue on the YouTube app (but not YouTube TV) with regards to multiview and RedZone. If you don’t have NFL RedZone, you may still see it listed in your multiview options on Home, but then will see an error message and won’t be able to watch the RedZone stream. YouTube says, “we’re sorry this is a confusing experience and we’re working to fix it. For now, don’t select the multiview options that include RedZone if you haven’t signed up for RedZone.”

3:45pm ET: By far the biggest issue I am seeing reported by users is how they select the home area or current location in YouTube TV. Many are reporting they are following the instructions YouTube has provided but it’s still not working for them.

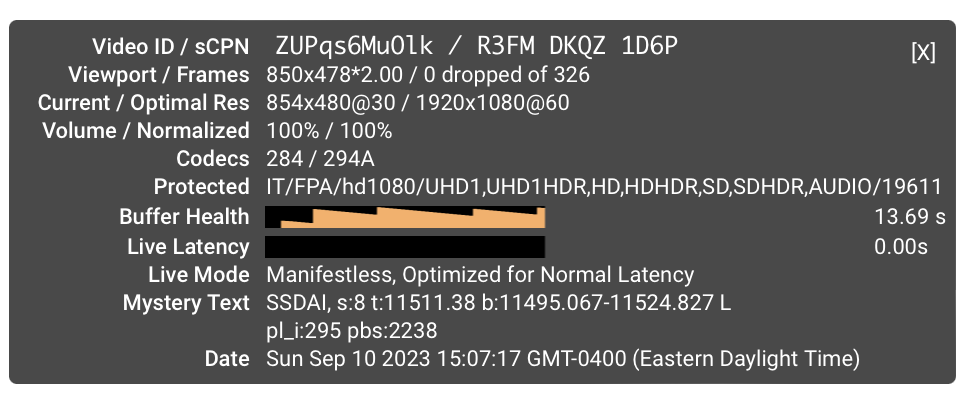

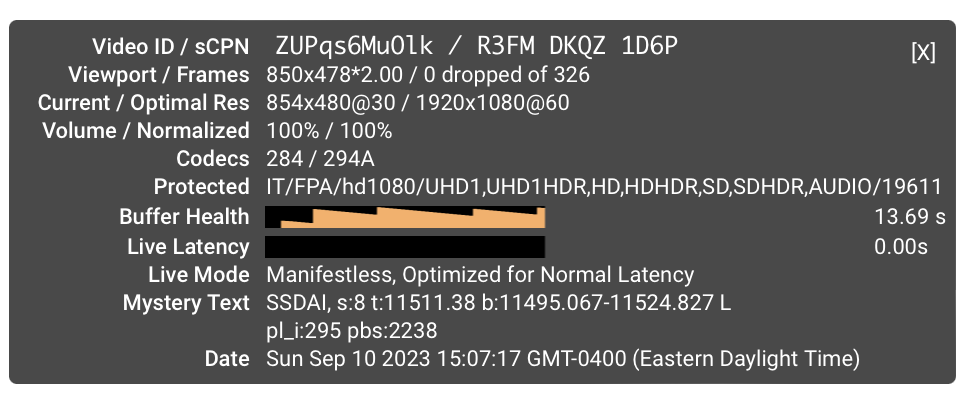

3:25pm ET: I am seeing latency of between 20-30 seconds depending on the device being used. Here’s some stats from the desktop on the Mac. And for those that will say this is a problem for YouTube and they need to use “ultra low latency”, they don’t. They are not losing out on sign ups due to the latency.

3:03pm ET: Two hours into the kickoff and from what I am seeing and from what is being reported by users, YouTube’s streams are looking good. Multiview is working well and I’ve not had any of the streams stop or buffer across the 3 TVs I’m testing on.

2:30pm ET: There are multiple reports of users having problems with regards to concurrent stream limitations. I don’t know how widespread this is but I have seen a limited number of complaints since the games started.

2:15pm ET: While it appears that YouTube’s live streams are looking good for the majority of users, the same can’t be said for users trying to watch via Comcast’s Xfinity stream app. It is suffering a major outage which took place right as the NFL games kicked off. At 2:02pm ET Xfinity acknowledged the outage on Twitter, but only in replies to users, they have not posted anything on their main feed. They said, “We are aware of the issue and our fix teams are engaged and doing everything they can to restore the Xfinity Stream functionality as quickly as they can.”

2:07pm ET: On the desktop, when you login to your account on YouTube.com you don’t even see any NFL games listed which makes no sense. YouTube’s own instructions for desktop say you have to search “NFL Sunday Ticket” or find the NFL Channel to be able to see the games.

2:00pm: Some users are saying when trying to stream it’s telling them to verify their location on their phone. But when they go to their phone and verify location and it still asks them to verify location on TV. Seems to be stuck in a loop. Seeing this reported [2] [3] across Apple TV and Roku.

1:50pm ET: Multiple users are reporting scrambled video of the Vikings game in particular. [2]

1:30pm ET: I see users saying they don’t know how to set their location when watching on a TV as YouTube needs your location to know what games are blacked out in your area. I was able to set it via my phone but others are saying it is not working for them. I am seeing many complaints of this.