Detailed Netflix Engineering Post Describes the Custom Origin Server It Built For Live

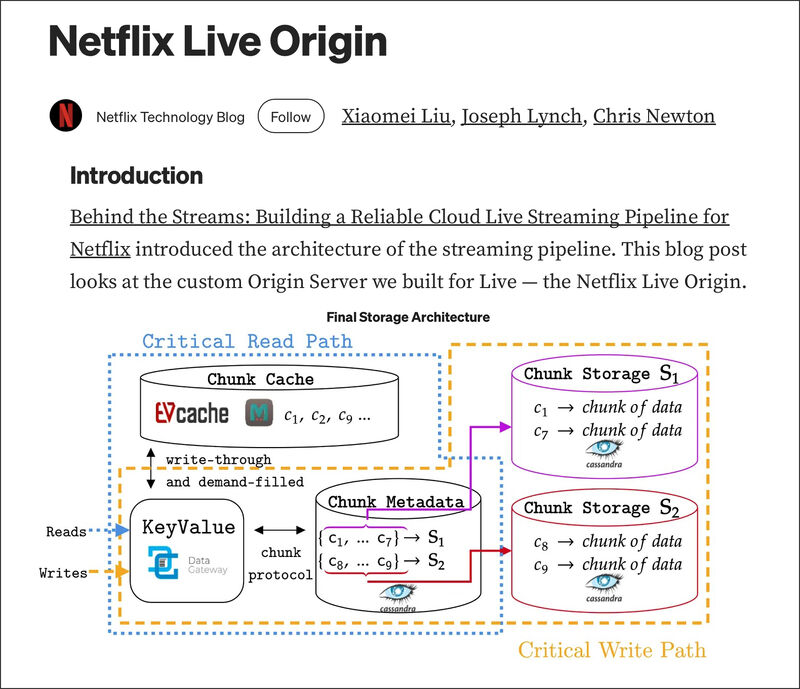

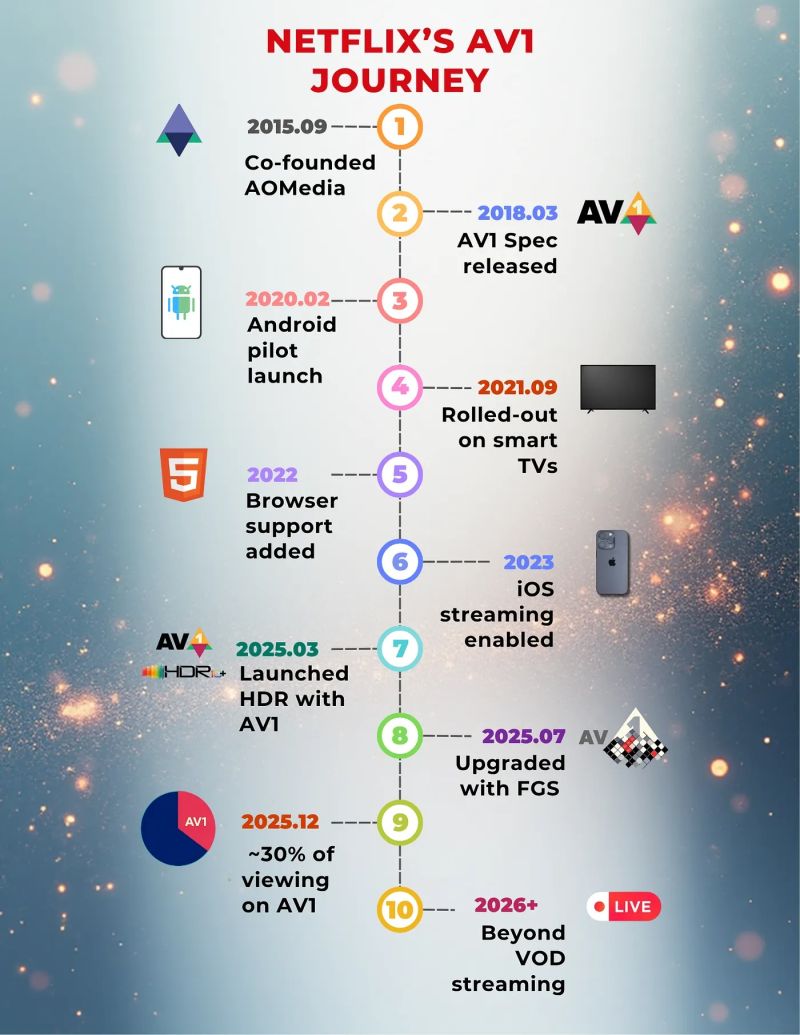

In one of the most detailed blog posts yet [3,200 words], Netflix describes the custom Origin Server it built for live. The sentence I like most states that Netflix took a platform originally built for VOD and simply “extended nginx’s proxy-caching functionality to address live-specific needs.” This goes against those who claim that Netflix can’t deliver live streaming at scale because it “wasn’t built for live,” and of course, contradicts all the public viewership data, with Netflix having successfully streamed live events with an AMA number in the tens of millions. There is so much great info in the post, so here’s just a few things I wanted to highlight:

➡️ Leveraging Netflix’s microservice platform priority rate limiting feature, the origin prioritizes live edge traffic over DVR traffic during periods of high load on the storage platform. To mitigate traffic surges, TTL cache control is used alongside priority rate limiting. When low-priority traffic is impacted, the origin instructs Open Connect to slow down and cache identical requests for 5 seconds by setting max-age = 5s, and returns an HTTP 503 error code. This strategy effectively dampens traffic surges by preventing repeated requests to the origin within that 5-second window.

➡️ Netflix’s combination of cache and highly available storage has met the demanding needs of its Live Origin for over a year, and the solution they built was significantly more expensive, but minimizing cost was not a key objective, and low latency with high availability was.

➡️ Netflix uses failover orchestrated at the server-side to reduce client complexity, with resilience achieved through redundant regional live streaming pipelines and implements epoch locking at the cloud encoder, which enables the origin to select a segment from either encoding pipeline.

➡️ Netflix’s redundant cloud streaming pipelines operate independently, encompassing distinct cloud regions, contribution feeds, encoder, and packager deployments to substantially mitigate the probability of simultaneous defective segments across the dual pipelines.

➡️ Millisecond grain caching was added to nginx to enhance the standard HTTP Cache Control, which only works at second granularity, a long time when segments are generated every 2 seconds.

➡️ Netflix’s enhanced cache invalidation and origin masking enable live streaming operations to hide known problematic segments from streaming clients once the bad segments are detected, protecting millions of streaming clients during the DVR playback window.

You can read the entire Netflix blog post here.